Marist Still Is Not Excluded: A Case Study of the College's Title IX & Campus Sexual Assault Climate

- Luke Carberry Mogan

- May 22, 2021

- 47 min read

Updated: May 30, 2021

Student advocacy groups and campus organization representatives at Marist College reportedly began meeting with school executives starting Friday, April 23. These roundtable discussions are vehicles for student leaders to communicate the worries had by peers over the Marist Title IX office’s understaffing, funding, and unreliable reporting system for sexual assault.

The general consensus had by campus residents is the department’s inherent flaws prevent them from placing trust in school officials, and undermine notions of maintaining a “safe campus” for all who live there.

Photoshop by Luke Carberry Mogan

The Meetings

The student voices attending these meetings are comprised of senior Samantha Williams, co-founder of activist organization Marist Stand Up Speak Out; junior Kevin Sayegh, co-founder and president of the Marist Moderates; and junior Claire Simonson, co-president of the Purple Thread support group.

Their objectives ranged from opening up constructive discourse on the Title IX office’s resources - it currently only staffs one interim employee - and its effectiveness, to installing a Student Title IX Advisory Board with student officials undergoing the same professional Title IX training faculty are certified through.

“We [also] proposed ideas of half-semester freshman year seminars…on bystander intervention, sexual-assault awareness, and providing more resources as everyone needs to know these resources are available,” Sayegh stated.

Marist administrators present for these meetings included Vice President and Dean for Student Affairs Deborah DiCaprio ; Director of Safety & Security John Blaisdell ; Vice President for Human Resources Christina Daniele ; Director of Student Conduct Matthew McMahon ; and the university’s legal counsel Sima Ahuja.

None of the above authorities could be reached for comment for this article. It is unknown if it is college policy to have legal counsel present for these types of meetings or pertained subject matter, as Ahuja was amongst a speaker panel for a student-organized sexual assault awareness workshop on May 14.

Interim-President Dennis J. Murray was unavailable to attend these meetings.

The school officials seemed especially receptive to the Marist Moderates president’s suggested implementation of his club’s Student Title IX Advisory Board.

The Student Title IX Advisory Board was conceived during a Marist Moderates board meeting on March 31, the same day extensive accounts of abuse by a now-expelled Marist student-athlete, Bryan Vargas, became publicly known on social media via a petition made by a victim’s family member.

“We had a meeting that night, every single one of our board members stayed on to lay out a plan on how we can get this adjusted on campus,” Sayegh said, detailing how no one logged off Zoom until the idea for the advisory board was properly sculpted and developed.

“We’re not expecting to cure campus of sexual assault, we’re trying to bring in student representation so Title IX supports students in the future instead of turning them away.”

The Marist Moderates board created a Change petition on March 31 - an immediate reaction to the Bryan Vargas scandal - to gain support for their vision of a student advisory board. It has gotten over 900 signatures since then.

Sayegh wanted student peers to receive the same eight-hour training seminars full-time Title IX employees receive from federal officials.

“[This should] be...separate from the Student Government Association (SGA) and other clubs, inside Marist infrastructure, intended for all students elected to the board to go through that training,” Sayegh noted. “We don’t want a board that’s just there just to be there, we want a function, a board that has an influence over Title IX.”

The Marist Moderates petition for a Student Title IX Advisory Board

Daniele, whose other executive positions include interim Title IX coordinator and the college’s affirmative action and equity coordinator, told the Marist Circle about how federal guidelines shape the reality of Title IX procedures:

“The federal and state laws dictate how the process needs to be. If the intent of an advisory board is to potentially develop process, that’s not really something that is afforded to us under the current law, and the way that they’re written.”

Daniele also added that students have been involved in the Title IX office before under research, programming, and training capacities.

In later meetings, Sayegh acknowledged the Marist officials’ cooperation in wanting to install a Student Title IX Advisory Board, hopefully even by this upcoming school year. Yet he found Daniele and her peers to appear to be initially dismissive or skeptical in the first listening session.

“Christina Daniele said...students have brought up similar ideas in the past, and the reason why it’s not implemented is because students keep graduating,” Sayegh recalled.

“Though it is not because we keep graduating, but because they don’t carry it on: when we start something, we plan on starting something to better and help future students. It’s imperative these infrastructures stay in place.”

Optimistic and hopefully indicative for the future, near and far, Sayegh and Simonson have supposedly begun working more closely with DiCaprio and other officials in laying out the groundwork for the advisory board endeavor.

“All the students working on this are ready to put in the change now, we just have to wait for Marist to officially implement,” Sayegh stated.

Williams indicated the administrative team repeatedly placed responsibility of creating protections for students on the students themselves. Her newly-established Stand Up Speak Out protest group organized several in-person protests on the Marist Green in April.

“One major thing they kept stressing in the round table was that it is on the students and not them to make change within the Title IX office,” Williams said.

“They kept saying that we, as students, have all this passion but then students leave and nothing happens. But we made sure to point out that it's not on us, as students that pay to go here, we expect to be protected by our own administration and not have to do it ourselves.”

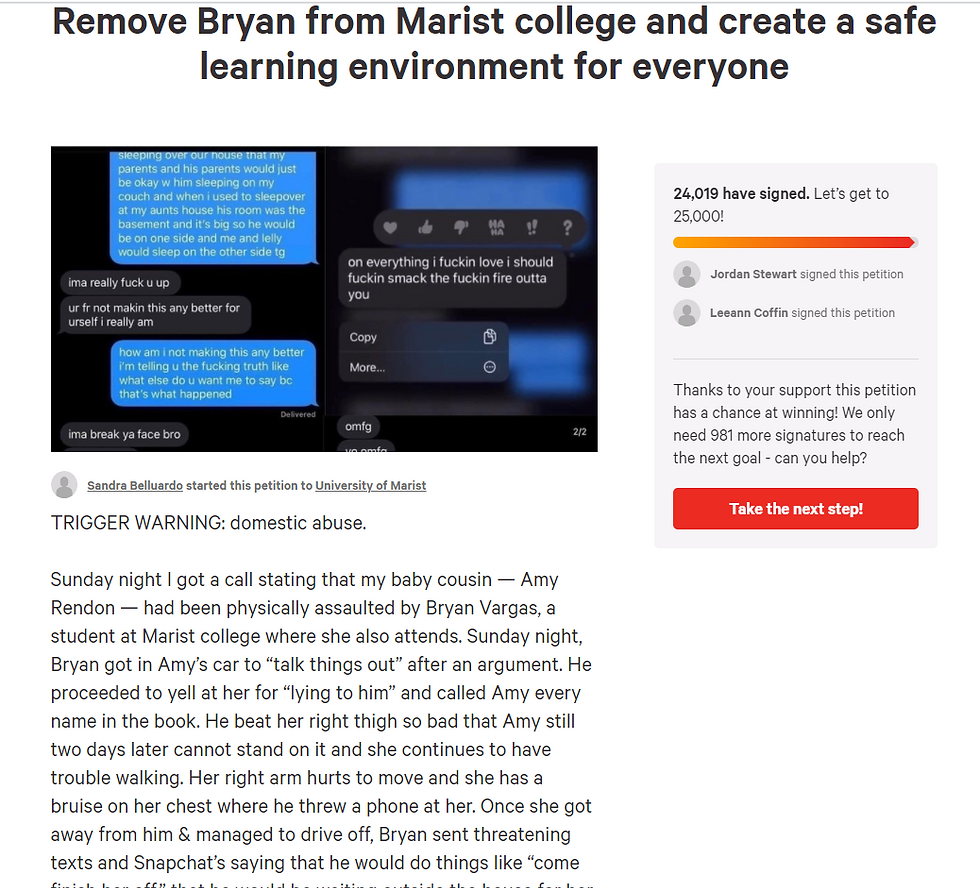

Petition created by Amy Rendon's family to have Bryan Vargas removed from Marist

The Petition

On March 30, family of Marist freshman Amy Rendon began campaigning on social media to alert the Marist community to the abuses Rendon faced while involved with now former football player Bryan Vargas.

Rendon’s uncle commented on a Facebook post by Marist Athletics, describing how the family had to take his niece to the hospital on March 28 after she could hardly walk from Vargas repeatedly hitting her: “...All you have a sister, daughter, niece, cousin and a Mother too...and you know this is totally unacceptable…”

The same day, Rendon’s cousins published their Change petition asking for Vargas’ removal from Marist College. The petition garnered over 16,000 signatures in the first 24 hours. A month and a half later, the petition now holds over 24,000 signatures.

The petition told the extent of Rendon’s abuses, from aggressive bruising found all over her body to her limited mobility and difficulty moving her right arm. Vargas sent her death threats, insinuating he’ll “come finish her off”, manipulating her in the past to stay with him, isolate from others, and confide in no one the trauma he inflicted.

Rendon’s cousins outline the grim truth, seeing the situation for what it is:

“At 19-years-old, Amy is a victim of domestic abuse.”

The petition circulated amongst student groups by the time Marist even responded to the allegations in the late morning of Wednesday, March 31.

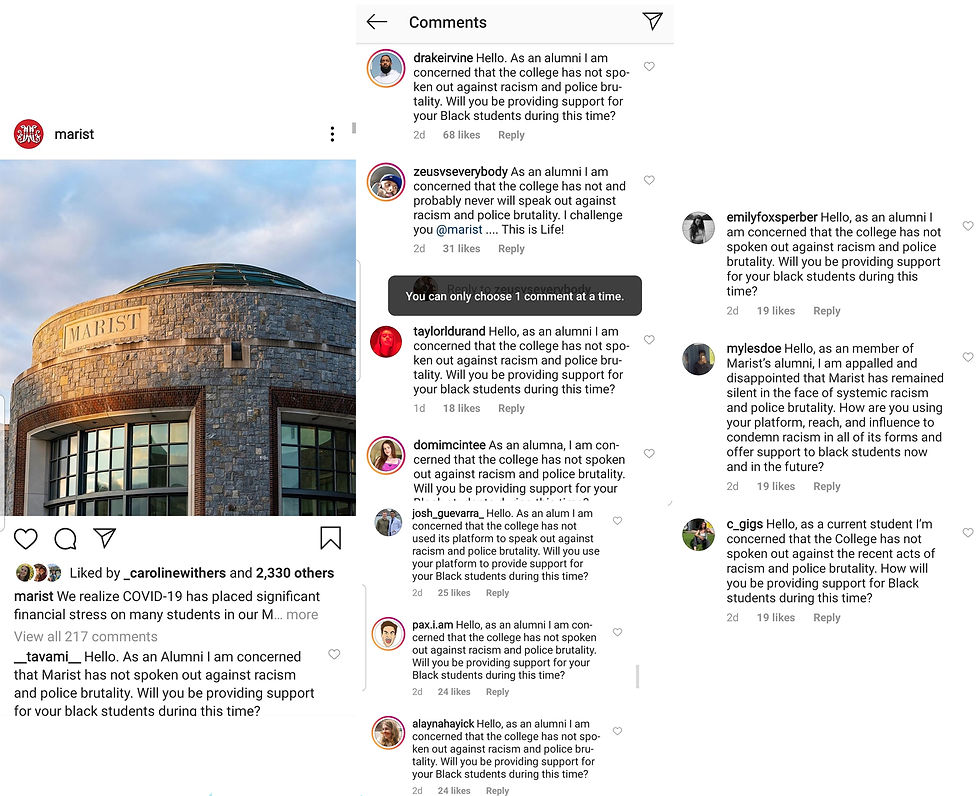

The Marist College social media posted a photo of the campus rotunda with a response to the allegations many students did not find confidence in, much due to its abruptness:

“The College has been made aware of an incident, which took place off-campus, and is fully cooperating with law enforcement in this matter. At this time, Marist cannot comment an on-going legal investigation. Marist does not condone assault and strongly encourages the reporting of incidents such as this.”

Associate Vice President of Marketing and Communication Alexa D’Agostino shared with Samantha Williams a first draft of the post’s caption from the afternoon of March 30, to prove the Marist Media team was proactive in attempting to address the assault allegations before they went viral.

The truth of this does not necessarily matter, as they idled until after the petition gained traction. Either way, they still kept the disputed clause stating their “awareness” to the incident, despite Vargas having other assault claims and ineffectual restraining orders against him.

Julia Fishman, the now former director of media relations at Marist, officially resigned from her position the week of April 30. Her automatic email response said her departure was “for another opportunity”, which cannot be entirely confirmed. D’Agostino had been designated to fill the role of media liaison in Fishman’s absence, but was not available to comment.

The fact the vicious attack occurred off-campus and in New Jersey apparently hindered the school’s ability to investigate and assign disciplinary action, as Rendon’s family were forced to seek out a thorough investigation through police involvement, a process many victims can attest to being far more draining than a Title IX investigation.

Both of Marist's social media posts from March 31

The Rendon petition highlighted the fact that Marist’s Vice President, Security Director Blaisdell, and interim Title IX Coordinator Daniele all communicated to the family that a Title IX investigation was impossible because the assault had happened off-campus.

The “jurisdiction” of Marist Security and other investigatory departments is a concept malleable for various scenarios, something many student critics voiced while campus activity was paused due to a COVID-19 spike. Marist Security had been alleged to be patrolling off-campus residential areas this semester in an effort to curb social gatherings and parties, despite the students living there paying to not be a part of the Marist campus ecosystem.

Multiple commenters on the Change petition page stated their own experience with Vargas and that their No Contact and restraining orders filed through the school were entirely ineffectual against him.

“Seeing the Bryan Vargas [petition] explode is not surprising at all, none of what happened or what Marist did surprised me,” said sophomore TJ Scarpa. “They never stood up, really stood up for their students, and it shows, taking a petition three times the size of the student body to [convince them to take action].”

Around 9:30 P.M on March 31, almost 12 hours since Marist’s radio-silence following their initial post, their social media updated to reveal the results of their heavy deliberations: “the student accused of the assault is no longer a student at Marist College.”

While the administration took the entirety of the day to mull over the decision to expel Vargas, the entire Marist community continued applying pressures in social media comments sections and stories, in petitions, from dorm rooms and beyond.

Many women were finding the strength to tell their stories of surviving assault and abuse in these online forums. Alumni discontinued their annual donations to the Marist Fund, pledging their money to advocacy and support groups for assault survivors, urging others to do the same. The Marist community had publicly come together to support one woman - a classmate, peer, and human being - whose experiences within private institutional structures evidently reflected that of many others' as well.

The rest of the second post’s caption included a lengthy blanket statement from DiCaprio and Daniele, featuring a just as long list of resources students are encouraged to consult when experiencing domestic abuse or sexual assault. Observers critiqued a majority of the content and rhetoric used in this statement should have been featured in the one Marist issued that morning, instead of a plain “No Comment” that was left open for interpretation.

"[That first post] should have been met by providing [those] resources, posting an entire 'how your report abuse' guide," Kevin Sayegh said, commenting survivors and victims reached out to the Marist Moderates regarding resource availability. "Marist should be openly marketing the resources they have - counseling services, the Title IX staff - ... but they have been treating it as a [public relations] issue, instead of as a campus safety one."

A multitude of student organizations and clubs filled the gap between Marist’s statements by making available resources for victims and counseling services known through social media and story posts.

“I was really impressed by how the Marist student body handled it, and how fast the petition blew up, I was one of the first 200 to sign,” said an anonymous student going under the pseudonym of Kat. “I was proud of how the students reacted and how no one was gonna let this get swept under the rug.”

Bryan Vargas’ profile on the football team’s roster was unavailable through the Marist Athletics website despite still appearing as a Google result. Consulting the Wayback Machine - a website that archives past versions of web addresses - it could be confirmed it was indeed Vargas’ athlete page, and past catalogs of the web address noted it had been altered in the late morning hours of March 31.

Marist College’s second statement was featured on all forms of social media, but the first statement failed to publish on Facebook that morning. Despite commanding the heaviest follower count among its social media, Marist did not post their three sentence statement to its 34,000 Facebook followers, a platform one would assume to possess the densest user population of tuition-paying parents and family.

Katherine Posada, one of Rendon’s cousins, thanked students and the college community for supporting her family in a video posted by activist group Students Revolt, agreeing with many sentiments held by student masses.

“[Marist] should trust the victims, they should trust the survivors, and they should listen to them,” Posada said. “I just wanted to say that I stand with you guys, thank you all of you , you guys have no idea but you are all the reason why Amy can continue to be so strong, and can smile now.”

Marist Athletics and Marist Football's acknowledgement posts and statements.

The following day on April 1, the Marist Athletics and Marist Football social media pages released statements condemning Vargas' actions. Marist Athletics included a list of national, New York state, and local resources for victims and survivors to consult. Both posts included graphics of ribbons corresponding with relevant movements, such as the purple domestic violence awareness ribbon or the Set The Expectations ribbon which combines purple with the teal sexual violence awareness ribbon.

On the Change petition page, athlete-alumni disowned Vargas, renouncing associations they may have shared as inter-generational teammates. Current Marist football players shared the Set The Expectations ribbon - a campaign for survivors founded by Brenda Tracy - on their personal social media. Vargas' former teammates expressed their solidarity with the victims and the rest of the campus, and stipulated certain procedures may prevent the football or athletic programs from directly addressing the allegations.

"We don’t stand for this and when this officially came out and we all started hearing about it, we all had conversations, we all were furious that this even happened," a group of football players said at a Marist Stand Up Speak Out protest. "We can never be in your shoes, but we just want to tell you guys that we stand with y’all and will be with you every step of the way and we don’t stand for that type of behavior."

This is not the first time a Marist football player was involved in a criminal investigation. In November 2018, the Marist Center Field noted several athletes had been escorted away from a weekday practice by campus security and Student Conduct Director Matt McMahon for unknown reasons. In a follow-up piece, the publication revealed three freshman players faced disciplinary charges for being involved in the theft of personal properties, such as sneakers and laptops, from Marian Hall residents.

The three were subsequently removed from Marist Football's online athletic roster, and a security guard commented to one of the theft victims: "Let's just say some players on the football team won't be attending Marist anymore."

The Town of Poughkeepsie Police Department refused to comment further on the charges "due to an ongoing investigation and/or" pending court dispositions.

Marist's overall athletics program houses 21 men's and women's sports teams. There are 17 separate school-sanctioned social media accounts to promote them, some of which represent both men's and women's programs or even group year-round athletes like cross country and track and field together. Of these 17 official accounts, only four made posts related to sexual or relationship violence: Cross Country-Track/Field, Football, Volleyball, and the general Marist Athletics page.

Author's Note, 5/29/2021: Marist Athletics has coordinated social media campaigns across all men's and women's accounts before. On August 4, 2020, the 17 collegiate team accounts promoted the recent inception of the Marist Black Student-Athlete Alliance, online and in-unison.

The main Marist College social media page remained inactive for the following two weeks after March 31, resuming activity to make posts celebrating future students who have committed to the school and honoring select faculty.

Understandably, change does not happen all at once, and social media does not present the broader picture of behind-the-scenes administrative action. But social media is the entry way to showing that one cares, it is the bare minimum and the least an organization can do. Students and campus club accounts had been relentless in sharing resources and their opinions online.

It presents a disjointed message when the track team with 800 Instagram followers puts in the effort to release a statement, where the lacrosse team with the audience of almost 5,000 followers does not follow suit. Student groups are left pondering: Is it asking too much to be inescapably loud with basic messaging?

"Not saying they don’t care about campus safety, but they haven’t taken it as serious as the student body has," Sayegh said about how Marist conveys itself through social media. "They should reflect how students are feeling in their social media, [we want them to] prove to us why we're wrong [about them], prove to us why they are [handling it right]."

Vargas’ recent activity on his Twitter and Hudl accounts imply his prospects to potentially transfer student-athlete eligibility to another Division 1 university.

Press conference held by student leadership on April 28

The Press Conference

The same upperclassmen who entered negotiations with Marist administrators organized a press conference less than a week later on April 28, to address the college’s failures in protecting students under alleged Clery Act violations.

Sayegh, Williams, and Simonson were joined by Stand Up Speak Out’s co-founder Catherine O’Brien, and Students Revolt co-founder Jahira Magnus. Another protest and advocacy group, Students Revolt gained notoriety by assembling a massive, impromptu student march at Marist following the Breonna Taylor verdict in September 2020.

“The amount of change needed goes beyond creating a student advisory board for Title IX," said Sayegh.

“In order to shed light on the specifics of these...violations, our goal is to address the frequent sexual assault and domestic abuse that happens on and off campus and the lack of support from the Marist administration in providing resources to survivors when instances of assault and abuse occur.”

Williams elaborated: " Marist has ignored serious complaints about students' behaviors, causing the dangerous sexual assault and domestic violence behavior to be further enabled and normalized only resulting in it escalating further."

Colleges accepting federal student aid must comply with the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act.

An audit of a university may be initiated by the U.S. Department of Education if “a media event raises certain concerns.” The press conference initiated by the united front of student leaders was covered by the Marist Circle, the Poughkeepsie Journal, and Bronx News12.

Conference speakers accused Marist of Clery violations by submitting its Annual Security Report two months late in December 2020.

“Contrary to the allegations, the college is in full compliance with all aspects of state and federal laws, including the Clery Act,” Marist legal counsel Sima Ahuja responded. “The U.S. Department of Education dictates when these reports are released and, because of the pandemic, extended the due date for the 2017-2019 report to December 31, 2020.”

Several legal sources and documents verify the deadline's extension, with some memos dating as far back as July 2020.

The Marist students also charge their school with non-compliance to the Clery Act’s timely warning and emergency notification clauses.

Timely warnings are issued when there is a serious or ongoing threat posed to the health and safety of the campus community, and the institutional body is obligated to release emergency notifications to students. This includes crimes, but also applies to inclement weather, gas leaks, fires, and contagious diseases.

“The allegations are completely incorrect,” Ahuja told the Marist Circle. “Every report brought to the attention of the Office of Safety and Security is assessed according to the criteria as defined in the Clery Act, and College policies and procedures.”

Photos from Marist Stand Up Speak Out's April protests

The press conference amplified the voices of students these organizations worked in representing, as Magnus revealed the first-hand failures she experienced with the Title IX office and the abuses she too faced as a victim of Bryan Vargas.

“My abuser was kicked off his program for about maybe a week, no more than two weeks,” the sophomore said in her account of her and her friends filing restraining orders against Vargas through Title IX.

A feature by the Marist Center Field examined Vargas’ previous confrontations and disputes with other female students in which he restrained one while screaming at her and punched a hole in a wall.

“There was one night prior to the incident on January 30, we had gotten into an argument, and we were walking on the campus green, and he punched me in my stomach. He slapped me a few times. And I remember I tried to run away and he grabbed me, and I fell to the floor. And then he picks me back up and he started to shake me, like, clearly aggressively. He literally just ripped the entire sleeve of my jacket off.”

Restraining orders were issued against Vargas for Magnus and friends including Skylar Segall after security intervened on an escalating altercation over claims Vargas stole a laptop, and saw bruising on the victim.

Even with the restraining order, Vargas resumed living next door to Segall in the Conklin Hall dorm, which would go on to be converted for COVID quarantine housing in the Spring 2021 semester.

When Segall contacted Marist about this matter, she was told she was the one that would have to move out and transfer to another dorm, not Vargas.

“He was really just an abusive person...manipulative…[and] we were all just threatened because of him,” Segall told the Center Field. “He has no regard for these women - they’re only looked at as punching bags [for him].”

Following his brief suspension from the football team, Vargas blackmailed the victim, threatening to send personal photos to her parents. She decided not to officially report the case to campus authorities.

The restraining orders achieved in providing neither safety nor security for victims and their support systems who were targeted by Vargas.

"As professionals, they should know the power these abusers and perpetrators have," Magnus said at the press conference. "It was such a mentally abusive, mentally draining situation. I was gaslit, I was manipulated and I was blackmailed to clear up the situation."

Other accounts of domestic abuse and sexual violence exist from Vargas’ previous partners, one even hinted at by his own mother.

All accounts of Vargas' behavior and aggression perfectly fit Marist Safety & Security's profile of a "Disruptive, Threatening, or Violent Persons."

“I tried to tell people a year ago about Mr. Vargas and no one listened to me - they turned their backs on me, and I was made out to be some crazy girl that was just too sensitive and wasn’t listening to her boyfriend,” Magnus wrote in a direct message.

“My friends and I, we tried so hard to tell campus, administration, his friends...about the type of person he was...no one believed me, so like we said: Marist did the bare minimum

In a conversation with Alexa D’Agostino, Williams recalled the Marist media officer repeatedly recommending Title IX subject matter be approached in a cautious manner in administrative meetings, as it is “people’s [personal] lives” or a “very sensitive topic.” Williams originally lobbied for her roundtable meetings to be made public, so as to let victims speak, be properly represented, and made immediately aware of university promises.

Though in the wake of these allegations with many more students emboldened to come forthright with their stories in very public forums, peers do not see the need for Marist's privacy in their policy decisions.

“It was a very public thing, everyone knew who it was,” Geandry Rodriguez, co-president of the Marist Black Student Union, said in reference to the petition which named Vargas and further rumors almost everyone had heard about him by then.

Daijia Canton, the treasurer to the Marist Black Student Union, was Amy Rendon’s RA in her residence hall. She recounts how she even witnessed Rendon first entering into a relationship with Vargas, and her attempts to try to talk to Rendon and her roommate about him.

“We knew the people [Vargas] had done all this too, and the school’s not listening again,” Canton said. “The school is saying [reports have] to be confidential, when the entire school knows.”

It may have been a rare case for Vargas' abuse and assault details to become so widely known, but victims of similar abuse by different abusers have been known to be open about them in safe spaces allotted by social circles and student groups/clubs.

"We are very big on 'what happens in FEMME, stays with FEMME' because we want our members to know that they can be honest with us and no one will go talking about it with anyone else," said Marist FEMME, a student organization founded on the education and empowerment intersectional feminism on campus.

FEMME described its mission statement as "essential bringing about conversation on...issues within our community on different levels." They pride themselves on being able to give students "...specifically girls on campus, a safe space to discuss these topics within a supportive family-like atmosphere."

FEMME's Instagram launched in April 2017, encouraging other like-minds to follow. Stemming from the national It's On Us initiative, the Marist College chapter cropped up in September 2018.

"On our end...I would definitely say...we foster a more safe and welcoming environment than Marist and Title IX offer," wrote Marist It's On Us president Grace Leavitt. "We believe and support all survivors and are working to make Marist a place where we can all feel safe and not worry that our school won't support us."

It’s On Us is a national initiative to combat campus sexual assault by engaging college communities to raise grassroots awareness and construct preventative education programs.

"The students and organizations bring these issues to the forefront of discourses...I'm happy many of us have been able to create safe spaces where people feel safe revealing these things and sharing their stories," Marist Democrats President Rosemary DaCruz stated. "Especially in the pandemic, these organizations are some of the only connection freshmen are getting...most of us as club leaders are working to craft those spaces."

Rendon’s cousin, Katherine Posada, applauded Marist students’ commitment to fighting for victims and campaigning for change on campus.

“I never heard anything but good things about Marist. To hear so many stories from girls in less than two weeks is beyond heartbreaking and I’ll do whatever I can to help Amy and every girl on campus feels secure,” Posada told the Marist Circle.

Amy Rendon's cousin Katherine Posada thanks the Marist community

The Admin (& Social Media)

Alexa D’Agostino had been instrumental in arranging the talks between fellow Marist officials and the student voices. Samantha Williams was contacted by D’Agostino when it became apparent through the Marist Stand Up Speak Out social media that she was one of its co-founders and key organizers.

D’Agostino was unavailable to comment, and many of these details are from Williams’ recollection and notes, which have been verified by other sources.

Williams remembers D’Agostino first reaching out following Stand Up Speak Out’s second protest on April 14.

“That’s when we realized we need to hit Marist where it hurts - the money, by yelling when tours were going by,” Williams said, as her group’s protests involved victims and students speaking through a megaphone. “I heard rumblings that Marist ambassadors [and tour guides] were avoiding the Green...asking if that was Sam yelling at potential families and students.”

When Williams’ influence as the point-person at these socially-distanced protests became obvious, it appeared Stand Up Speak Out may need approval from the college to continue their activities. The school re-extended its campus pause multiple times as the college was still experiencing a COVID case spike at the time. In their posts, Stand Up Speak Out made it very clear their intentions to abide by social distancing guidelines on campus.

Stand Up Speak Out later opted to have Student Revolts plan future demonstrations to maintain their grassroots message, as they did a campus march full of chants on April 15.

After receiving an email from D’Agostino, Williams figured there was nothing to lose by corresponding and cooperating with a Marist official. Their correspondences progressed quickly and were soon texting and calling each other on how to execute the eventual roundtable.

“We have a lot we’re working on in the background and don’t need tours going around that we won’t protect them, we care,” Williams recited D’Agostino saying in one of their first communications. “If you don’t think we care, that’s insane, if you don’t think [President Murray] cares.”

This was a few weeks prior to Media Relations Director Julia Fishman’s resignation, from which D’Agostino has assumed to have become an interim replacement for.

From even the most casual of observer’s perspectives, Marist media had an especially burdensome past year. Former and present students have come out critical of how the school has visibly responded to controversies ranging from the Bryan Vargas petition to their handling of COVID conditions , international student housing , and delayed condemnation of the George Floyd killing.

The below photos are archived screenshots from a June 2020 post Marist deleted due to the negative criticisms it was receiving. While campaigning for donations for the Student Emergency Fund sponsoring students financially impacted by the COVID crisis, which mail flyers were also sent out for, the college had yet to comment on the Black Lives Matter or George Floyd movements.

Marist Media has always tried to include the school on progressive movements or dialogues, especially in mass email messages from college presidents on them, but stayed silent for almost nine days on the prominent matter that gripped the nation. Students and alumni voiced their discontent, so when the post reached over 300 comments demanding the college stand in solidarity with community members of color, the post was deleted

"We were being respectful of the feedback from our alumni,” Julia Fishman told the Marist Circle. “The decision to remove the call for donations was made out of sensitivity to that issue and not to silence anyone regarding the important issues of race currently facing the nation.”

The alumni Instagram account Red Foxes Against Racism sprouted from the online activist movement at the time. They saved a screen-recording of the deleted post, now demanding to know why the post was deleted: "“This is a clear act of censorship and if you were one of the people whose voices were silenced we’d ask that you once again comment on this linked post below. Don’t let them silence you.”

Screenshot and comments of a post from last summer Marist deleted, students and alumni were very critical of their silence on the George Floyd killing

Given Marist’s track record of not providing a conducive environment or available tools for victims to feel safe or heard, Williams’ chief concern became transparency. She wanted these discussions to be public, possible for students to watch and listen via Zoom or some recording, a way to put Marist administrators on record so as to hold them to promises they make.

D’Agostino seemed to be confrontational about this aspect, as it presented a liable risk for administrators the school’s legal department would not allow. Williams claimed D’Agostino accused her of “just wanting to blast Marist, [she said she] thought this was going to be a constructive conversation.”

“I don’t want to bash Marist, I’m not a victim or survivor so I’m not going to act [like I know their experiences],” Williams states, wanting to keep the people these policies affect to be a part of this conversation too. “We don’t want to speak on behalf of other people, just want transparency for [their sake].”

Communications between the two were constant, and typically confusing as date and times D’Agostino suggested for the first roundtable meeting were always changing. Scheduling conflicts can easily kill the momentum of movements and progress.

When a date was finally settled on - Friday, April 23 - Williams was emailed by interim-Title IX coordinator Daniele to confirm the in-person meeting. Williams’ demands from the start had been that the meeting be over Zoom, to which Danielle replied that D’Agostino communicated the students’ comfort in being in person.

Williams stated her and her peers were rescheduling or cancelling classes and job interviews to make this meeting work for them over Zoom. Danielle shared mutual confusion as to where a communication breakdown occurred.

Next, it appeared the agenda of information they were to present was not entirely conveyed to the roundtable faculty either, as they and D’Agostino were perplexed as to why the students wanted to read off accounts and stories from assault survivors and victims.

Williams summed up her experience with D’Agostino and her co-workers as being gaslit, feeling harassed by the Communications & Marketing officer. She summarized the executives’ feelings towards student movements as “always [being] passionate about these projects, [but] then they graduate.”

Williams and O’Brien’s Stand Up Speak Out is not the first student-run advocacy account to feel the weight of Marist or D’Agostino against them.

“We had an administrator [D’Agostino] messaging us constantly after every post we [made] and telling us to call them and reveal who we were,” wrote Me Too Marist, an Instagram page who publishes anonymous stories about sexual and dating violence submitted to them.

Me Too Marist posted five anonymous accounts of assault and abuse (unrelated to Bryan Vargas) in the weeks after the petition

All from Marist students, their content contains written instances of stalking, sexual harassment, emotional abuse, intimidation, drugging, sexual assault, and rape. The moderators of the page divulged they have about 30 submitted stories from anonymous followers they have yet to publish, and over 120 that have already been published on their page.

Me Too Marist explained D’Agostino messaged them “defensive[ly] and taking the stance ‘we do enough.’ “ Next, they alleged D'Agostino claimed Me Too Marist was in danger of a lawsuit from students accused in their posts. Me Too Marist does not name any alleged accusers in their posts, but do specify which sports teams or fraternity groups are involved with these incidents.

“Some individuals [from these groups] were very defensive and questioned the credibility of survivors,” Me Too Marist said. “But a lot of organizations, and especially the frats have asked us for tips...training resources/materials...on how to address these issues in their organization and were supportive."

There is an aspect of effective behavior modification that comes out of online activist groups such as Me Too Marist, suggesting Marist sports teams and fraternities adopt zero tolerance policies to "set a standard to show this behavior is not tolerated." It has periodically continued to post without any interference.

“She stopped...we just made our mission known and said we weren’t interested in revealing our identity,” Me Too Marist described their last digital communication with D’Agostino. “Basically, we nicely told them that we aren’t going to stop posting and basically to back off.”

Other student activist accounts are not as fortunate and may have allegedly succumb to administrative pressure. Early to mid-April, the BIPOC At Marist College page page was noticed to have been deleted or archived from Instagram. The account's heading was visible on April 13, but posts were blank, before the account was permanently deleted.

BIPOC AT Marist - BIPOC is short for “black, indigenous, and people of color” - was another anonymous account that shared students’ anonymous feelings and dealings with racism on campus.

“We noticed that too, right around the time time of the sexual assault and awareness [movements],” said Canton from the Marist Black Student Union. “People linked it to Marist not believing the stories of survivors, probably didn’t believe the stories of people dealing with racial discrimination…”

Another amplifier to unheard voices, BIPOC At Marist exposed the microaggressions and harassment students of color were dealt by not only other students, but even Marist’s own faculty.

A series of anonymous submissions explained the ways in which the college’s theatre program director, Matt Andrews, directed racially motivated remarks at students and overall perpetuated a toxic environment in the department.

A screenshot of the BIPOC At Marist College page on April 13, 2021, as it was being deleted (Right), a screenshot of the account's Story Highlights critical of the march (Left)

A petition to remove Andrews from Marist was created by students in July 2020 and has garnered almost 800 signatures. The Change page quotes a now deleted BIPOC At Marist post stating Andrews said to an African-American student sitting in the front of class: “don’t pull a Rosa Parks on me now!”

“He is currently my teacher, had him for two semesters in a row...and was the only black or person of color in that class,” Canton said, stating how she included all of the above information in her end of course professor reviews. “He said he read all of our [anonymous course performance] reviews and looked at me directly.”

Marist acknowledged the facts BIPOC At Marist brought to light in a formal statement, naming the account, and stating that they “take allegations of harassment, discrimination, and microaggressions very seriously, and such actions have no place in our classrooms, on our campus, or in our college community.”

The statement went on to say: “At Marist, we stand by our BIPOC students and we strive to create a welcoming atmosphere for everyone. We encourage students to come forward with types of issues described here...In this way, we can help to foster a culture where everyone feels included, heard, and valued.”

The Marist Theatre Program’s student-run Instagram released a statement in July 2020, apologizing for Matthews’ actions, hoping to generate a safer environment for future members. Matthews is currently still employed at Marist.

"With Marist, you have to record everything at this point, in order for you story to be heard," said Black Student Union co-president Khmari Awai.

In the official release from Marist, links to online discrimination forms were included, yet again noting the responsibility is on the students to report these issues so Marist can take action. Students shouldering the burden to hold the institution accountable is an overwhelming theme in most aspects of the university.

The same language is not exclusive to Title IX cases or reporting racist faculty. Marist has repeatedly pushed the idea of students being their own agents of urgency when policing other students for COVID guideline violations they themselves won’t enforce or demanding improvements to diminishing quality of life standards in housing and the dining hall.

And just like those other areas of campus life, when students do file claims, they are only heard momentarily, before the status quo resumes. Matthews still works at Marist, so nothing has changed.

“As a person of color, I’m sure I speak for others when I say that the BIPOC page was a safe space - hearing what others had to say gave me the courage to speak up and submit my experiences,” said sophomore Karina Brea, an early founder of Students Revolt. “I finally felt seen and not alone, as it’s hard to not feel alone when you’ve been singled out your whole life.”

The creators of BIPOC At Marist are still unknown, but the team behind Me Too Marist hypothesized the other account may have been intimidated by Marist faculty, just as they were.

When the Black Student Union (BSU) met with Interim-President Murray and other school executives over Zoom last semester, they read off student experiences found in BIPOC At Marist and Me Too Marist posts. BSU board members remembered how shocked Murray was to hear all of these details, compounding on student speculations about how disorganized campus administrators are with their hierarchy of information distribution.

Representatives from Red Foxes Against Racism met with Pres. Murray in June 2020 and offered curriculum and infrastructure proposals similar to Sayegh and the Marist Moderates' Student Title IX Advisory Board, including implementing classes, reporting systems, diversity representation in the college administration.

In September 2020, BIPOC At Marist was critical of the racial injustice march Marist had sponsored and worked alongside student groups like the BSU to organize. Many students ended up having mixed feelings about the event, which many described as a photo-op for Murray and other Marist leaders.

BIPOC At Marist had an entire Instagram Story Highlight dedicated to the responses they received from other students. Many attendants had been apathetic towards the cause, coaches forced athletes to show up and march, inflammatory remarks about the Black Lives Matter movement were overheard. The march felt disingenuous and it showed through what BIPOC At Marist captured.

When trying to plan future events or roundtable discussions, the BSU found themselves receiving the cold shoulder from Marist’s higher-ups.

“Murray has department heads for a reason, they should take the responsibility to contact us...we’re still waiting for their email, months later,” BSU co-president Geandry Rodriguez said. “Even if it isn’t Murray or the rest of his administration, they’re still not taking the initiative to make the safer campus they want to create.”

In an interview, Williams attributed both Me Too Marist and BIPOC At Marist for helping to document these widespread - not so isolated - mishandlings of assault and racism.

“We did start [Marist Stand Up Speak Out] as a result of the Bryan Vargas case, but that was really only a catalyst to fully realizing the terrible climate Marist has for sexual assault and domestic violence,” she said.

In the age of accountability, the use of anonymous accounts restore ownership of narratives on these issues back to the students inhabiting an environment they do not feel heard in. Sometimes they are the most direct route to feeling recognized and comfortable. A last resort when universities ignore these issues or, in Marist's case, strives to reach for national narratives in Town Halls that do not entirely address what is happening locally.

"They need to understand that they need to give us the space to talk about our own campus, as much as the bigger issues matter," Brea said. "They need to hear it from us instead of generalizing the whole topic."

When attending college, there is not only a social contract, but a literal financial obligation for these institutions to provide quality of life experiences and an environment of safety and stability. Marist students are paying over $60,000 for tuition and room and board, and yet a majority of them agree the school is doing far from enough to protect them.

“This is a legal thing... I don’t understand why schools investigate this stuff,” Williams remembers D’Agostino explicitly saying, which has been confirmed by other sources.

“Law enforcement should be doing this, it doesn’t make any sense since we have no control over it.”

A patchwork of Marist's reporting, security, and counseling programs/tools

The Investigator(s)

Marist should prioritize the safety of its students from potential threats, as not only a business but an educational body responsible for the welfare of its participants.

In April 2018, nearly all Dutchess County police departments - 13 out of 15 - had completed their Lethality Assessment Program (LAP) training. Officers trained under LAP are educated on how to gauge potential for escalating violence in domestic abuse cases through an 11-question survey. Factors such as abuse history, death threats, abuser’s emotional stability, and abuser’s possession of a gun alert authorities of future danger, allowing them to recommend counseling and shelter services to victims.

Victim protection is one half of the issue as, according to a RAINN study, 975 perpetrators out of 1,000 sexual assault cases are likely to walk away free. Additionally, nearly two-thirds of sexual assaults go unreported, subsequently due to the low conviction rates in similar cases.

“I was never instructed not to call the police, [but] from my perspective it seemed Marist tried to keep matters internal whenever possible...with zero follow through,” said former RA Roberto Hull who stated other legitimate felonies committed on campus were passed off or unresolved. “As a result there was an atmosphere where sometimes very serious infractions were met with minimal consequences.”

Anonymous Marist residents illustrated having no idea where to start with filing a police report, let alone a Title IX report, against an abuser and unaware of any such school resources that would guide them through such processes.

So reporting an assault through Title IX is viewed by many as the next best option, warranting hope for disciplinary action.

“Considering Marist’s competitor institutions have double to triple the amount of full-time staff in their Title IX offices, this is truly unacceptable and is a clear indication of Marist’s priorities,” Williams said in the April press conference. “This needs to change.”

Local private universities like Vassar College - who boast vastly more substantial endowment funds compared to Marist’s - do their best to make their Title IX staff publicly known, dedicating an entire web-page with staff profiles to the office.

Now, Marist’s only Title IX employee is interim coordinator Christina Daniele. Her background - psychology, criminal justice - and experience - child welfare and counseling services - certainly qualify her for the position, as well as being a certified Coordinator and Investigator by the Association of Title IX Administrators (ATIXA).

It is Daniele’s other responsibilities at Marist that worry students about her full-time commitment to the Title IX office. To reiterate, she is also the vice president for the human resources department, as well as the college’s affirmative action and equity coordinator. Daniele was not available to comment, so if and how much she has to juggle multiple hats of executive roles is unknown.

Toya Cooper was Daniele’s predecessor as Title IX coordinator and Director of Equity, Inclusion, and Compliance. Her tenure at Marist only lasted from July 2019 till July 2020, when her departure demanded Daniele step in as interim coordinator. An attorney, Cooper held a longstanding position as legal counsel to Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, for 18 years before migrating to Marist.

Kaleigh Malavé had been Marist’s Title IX investigator since July 2018. Possessing a masters degree in college student affairs, Malavé has a bountiful list of achievements and experience that qualify her for the investigator role. She has the same ATIXA certification as Daniele, paired with ATIXA certifications as a Level 1 and Level 2 civil rights investigator. Her young age and array of practical experiences working directly with students makes her sound exponentially more relatable to the modern college experience, an advantage for a department most students see as out of touch.

Malavé was promoted to deputy Title IX coordinator in October 2019, working in stride with both Cooper and Daniele in that time, until her sudden resignation from Marist in April 2021. She was unavailable to comment.

Currently, Daniele is the only full-time Title IX staff.

Marist Title IX job listings and descriptions

The two job postings for the department’s Title IX Investigator & Outreach Coordinator and Director of Institutional Equity & Title IX Coordinator - both the roles Daniele is filling - can be found on Marist’s Office of Human Resources career site. Both were posted on April 21.

Both positions require deep understanding and compliance to Clery Act, Title IX guidelines, HIPAA health provisions, New York state laws, and other legislative lining relevant to public policy praxis.

ATIXA certification is required for the investigator-coordinator position, but not for the overseeing Equity & Title IX coordinator. Much of the responsibilities overlap: reviewing complaints/cases, structuring training for staff and faculty, assessing areas for improvement, implementing campus surveys, managing web-page and social media communications.

The investigator is more hands-on with handling case evaluations and leading information gathering, with minimum requirements listing experience with “Title IX compliance, law, human resources, student life, student conduct, or related field[s].” It is highly preferred for applicants to have “experience in conducting trauma-sensitive investigations in a higher education setting…”

The Equity & Title IX coordinator is also afforded diversity in applicant experiences, as those with master’s degrees in “human services, law, criminal justice, higher education, or a related field is preferred” and “an advanced degree in law, JD or doctoral degree is strongly preferred.”

None of the past or current Title IX coordinators and staff were available to comment, so it can only be speculated on how these broad qualifications may influence the type of leadership in Title IX. Coordinators and investigators are restricted by Title IX procedures and federal laws, but someone with a legal or law enforcement background may exhibit different perspectives than someone with practice working in education or victim advocacy fields.

The leadership sets the tone for the future, as the essential functions of the investigator role include “actively supporting a College community that fosters a climate of safety and equity.”

“Our perspective on the sexual assault climate is that the Title IX lacks the resources to fully support its students properly,” Williams wrote, denoting Daniele’s interim role as the only staffer to be troublesome to a campus of students who have already indicated issues with reporting and assault culture.

“They really have a lot of resources, but they don’t offer [or advertise] them, and they don’t check up on students who report this stuff,” Canton said. “What if I report it, what’s going to happen? Nothing.”

Messaging through Marist Stand Up Speak Out’s instagram page, Williams depicted an anonymous submission the account received where Title IX “just did not follow through on the reporting process.”

“[The individual] reached out to [Title IX] and it took them a whole week to get back,” Williams wrote. “Then they completely blew off their meeting, [the student] was in a Webex [online call] room for 30 minutes before getting an email saying Title IX couldn’t meet until tomorrow.”

Marist Counseling Services showing their support while listing off external resources for domestic abuse and sexual violence survivors

In a statement made by Daniele following the press conference held by students, the human resources vice president said: “In addition to the Title IX office, the college offers resources and support, including the Marist Office of Counseling Services, to assist students in such situations.”

Dr. Marisa Moore, the interim-counseling services director, was unavailable to comment on mental health consultations the department provides during Title IX investigations. It is evident Marist’s mental health care providers do care greatly about meeting the demands of students and victims with the care they need.

Retiring former director and counselor Dr. Naomi Ferleger briefly commented: “We feel it’s great that the students are advocating for more resources and changes for things they see as problematic”

Adapting to COVID by offering remote sessions was projected to make regular mental health appointments more accessible, and an active social media staffed by student-interns certainly has Counseling Services being more proactive to make their abilities known.

But students still hold the opinion the department is understaffed and had difficulty in the past booking one-on-one sessions instead of the group therapy sessions that were heavily promoted.

“Fall semester my freshman year, I had an introductory [counseling] session, and it was just 20 minutes of being talked at,” said TJ Scarpa. “I felt bad because I could see how busy she [the counselor] was, there was [so few] of them and over 5,000 kids...not much individual time [for each patient].”

There are nine staffed counselors at Marist.

In the aforementioned statement, Daniele highlighted Marist College was in the midst of a national search process for the two Title IX positions.

“It’s very easy to write it all off and say [the Marist administration] doesn’t care, and I would like to hope it’s deeper than that, with its own set of challenges,” Scarpa said. “But they definitely can be doing a better job, Dennis Murray is still an interim-president, they’re trying to find a new president and a new dean for the school of management.”

The national search to find a successor to College President Dennis J. Murray - who had served full-time from 1979 to 2016 - took over a year and yielded a temporary solution. David Yellen’s time as college president lasted from 2016 until only 2019, after disputes between the board of trustees forced him out. Murray, who held an office above the library during Yellen’s stay, resumed duties as interim-president following Yellen’s dismissal.

“They’re filling their plate, but seeming to focus on the wrong things,” Scarpa felt.

In a 2014 Red Fox Report feature, explaining Title IX’s congressional origins, student affairs dean and vice president Deborah DiCaprio asserted “14 Marist administrators, including herself, have been trained as Title IX investigators.”

DiCaprio has been in students affairs management at Marist since 1982.

According to the same administrative sources at the time: “faculty and staff will be trained in their responsibilities under the law, and all incoming students will be trained in the law and policies as well.”

“I know that freshman year, everyone has to watch little videos and take little quizzes, but I believe that is the extent of the training,” Levitt of the Marist It's On Us, wrote in an Instagram direct message.

Marist It's On Us was planning a survivor march in April even before the Bryan Vargas case went viral

Under regular - non socially-distanced - circumstances in the past, extracurricular clubs sanctioned by the school had to have representatives attend Title IX advisory workshops. Basically a PowerPoint with hand-raising to answer questions about conflict intervention, attendants were rewarded with dining hall pizza.

“I am unsure of the other clubs, but we did not have to complete Title IX training for SGA,” wrote the Marist SGA account in an Instagram direct message. “However, every student is required to take a Title IX and alcoholism program online before coming in freshman year….student employees are also required to go through a similar workplace harassment training.”

Faculty and staff training and abidance falls under the realm of responsibilities encompassed in the vacant Title IX positions. DiCaprio was unavailable to comment, so the designs of training and workshops for full-time employees is unknown.

This is the same type of training Sayegh and the Marist Moderates are lobbying for student delegates to be tutored under for their proposed Student Title IX Advisory Board.

The 2014 Red Fox Report article cites Title IX, Student Affairs, Marist Security, and the Poughkeepsie Police as avenues to file assault allegations through. It can be assumed these departments employ ATIXA certified individuals capable of conducting Title IX investigations DiCaprio alluded to.

“There are also specific campus victim advocates, like Kayla Miller, who students don’t even know is a huge resource for them,” said Marist FEMME.

Miller’s work with Poughkeepsie’s Family Services enables victims a degree of comfort in having someone external from Marist’s infrastructure listen to them. Where as students purport to be seen through and left to navigate the reporting systems on their own by Marist authorities.

Her job entails managing casework, scheduling crisis counseling for victims, collaborating through local colleges and Title IX offices, and even accompanying victims and clients to hospitals, court hearings, police departments, and counseling sessions.

Ed Freer preceded Toya Cooper and Kaleigh Malavé as acting Deputy Title IX Coordinator from 2016 to 2019. Now a practicing attorney within Dutchess County, was also Marist’s assistant Safety & Security director for three years and a retired detective lieutenant with the City of Poughkeepsie Police Department.

Freer’s stay as deputy Title IX coordinator marks another example of a candidate’s exceeding qualifications as his involvement investigating assaults and other harsher crimes gives him credibility in researching campus assaults. He was knowledgeable in the laws surrounding Title IX, accustomed to structured information gathering and organized filing systems seen in police work.

His time as Marist Security’s operations director contributed to learning the campus, how authority and security patrols are dispersed, and, on paper, reads as an ideal legal liaison to oversee those willing to participate in the reporting process.

Unavailable to comment, Freer’s professional website for his law practice states he had “conducted over 150 investigations relating to alleged misconduct involving students, staff and faculty” while at Marist.

Marist FEMME summarizing Title IX's limitations that are harmful to student-victims

Previously insinuated - yet not positively confirmed - it is wondered if the backgrounds of Title IX leadership affect the ways the office carries out its mission going forward. Purely speculative, yet a factor that supplies students with enough skepticism to be hesitant to file reports with a security or law enforcement official than a trained crisis counselor who’s well aware of post-assault trauma.

“I was gone that night but my roommate was texting me saying that Title IX gave them such a hard time,” sophomore Karina Brea described her close friend’s experience reporting through security in 2020. “They reached out to them like an hour after the incident, and the security person who went to the dorm was very insensitive to the fact that the survivor had just been assaulted.”

It remains unclear whether any or all Marist Security officers are certified through proper ATIXA channels to carry out Title IX investigations and interview victims. Even when proactive, putting in the effort to respond to a claim, the Security team seems inconsiderate to the circumstances.

“[Security was] almost annoyed with the fact that she wasn’t completely ready to ‘rat out’ the assaulter, the security guard was like ‘well if you aren’t going to tell me who, then why am I here?’” Brea relayed her friend’s perspective of the events.

The student was still processing the assault, a traumatic and emotionally complex event, which the security official was insensitive towards.

“There was no good balance of ‘okay, she just went through this, let’s get enough information, but also not grill her,’” Brea wrote.

Scarpa witnessed Title IX ineffectiveness and restrictive bureaucratic methods it must abide by when helping a close friend through reporting an assault, going with her to the Title IX office.

For Scarpa’s friend, the security and student conduct figures’ messy handling of the accused perpetrator had disastrous social repercussions.

“They lived on the floor right next to each other, he was never moved and the No Contact order was [useless]...they couldn’t avoid each other,” Scarpa said. “The one time they brought him in for questioning, it was a busy Friday night when everyone was in the common room when the RD and security officers came through.”

Similar to Bryan Vargas’ victims, No Contact and restraining orders are reduced to performative actions that bare no consequential weight.

With Brea’s friend, security lacked patience for a victim. For Scarpa’s friend, security lacked discretion for the accused in a sensitive case area that could elicit rumor-mill musings for both victim and assailant.

“[They thought] ‘screw discretion’...and took him in in front of everyone, when no one else aside from the two of them or who they decided to include should have known what was going on,” Scarpa said.

Administrators define Title IX claims to be sensitive and personal matters, yet they themselves fail to achieve that balance, even for both parties. People come out of sexual assaults or domestic abuse feeling stripped of their identities. It should be imperative to Title IX’s duty to not only protect potential victims but also keep their identities intact, as the subject of an above public spectacle can quickly be reduced to just the latest gossip.

“It was not their business, and now it was everyone’s business. It was all people talked about for the next two months and the girl ended up transferring because of it.”

Marist Title IX's recommended procedures, notably official Title IX procedures asking victims to preserve and maintain evidence

The strain of preserving articles of evidence is additionally placed on victims, as Title IX's official legislative guidelines found on Marist's Safety & Security web-page ask students avoid all activities - even showering - that could alter physical evidence following an attack.

“Often, there’s more evidence than you think there is and we try to get the truth, we have an obligation to," Freer said in a 2018 interview with the Marist Circle. "The sooner the better to report. It makes it more difficult for Title IX because memories of witnesses fade, evidence may be lost."

He goes on to list categories of evidence such as swipe records, clothing, videos, witnesses, and text messages that have been collected in school investigations in the past.

The 2018 article Freer was quoted in featured interviews with eight anonymous female students testifying on the campus' rampant rape culture, several of which characterized the decision to report an assault as "draining."

Dr. Ferleger cited overwhelming feelings of shame, regret, and self blame resulting from surviving an attack as pertinent reasons for choosing not to report. Furthermore, it can be stressful and confusing when sacred social boundaries are violated and someone is raped by a friend or acquaintance.

"Victims have many reasons that they might not come forward. We have to accept that,” Freer said in conjunction with the sad truth many of these crimes go unreported on campus, and that campus statistics can only reflect what has been reported.

“Marist promotes student reporting but seems to not show students that they believe them or take their concerns seriously,” said Leavitt in a 2021 direct message. “But who would want to when Marist doesn’t believe them or respond to them in a timely manner?”

“I whole-heartedly disagree with students who think reporting is pointless. The time, energy and resources we put into this are enormous," said Security Director John Blaisdell in 2018.

Blaisdell and Freer agreed Title IX and Security can still aid victims without launching a full investigation - if the student does not want them to - by changing class schedules, housing assignments, and contacting professors to lessen the amount of potential contact they could have near an alleged attacker.

Referenced before, there has already been seeds of distrust planted between students and safety officials that have bloomed due to the No Contact and restraining orders having no effect in the past. Exhibited in Magnus and Segall's orders against Bryan Vargas and Scarpa's acquaintance, even tiny gestures that Security promises are ineffectual and even work against individuals feeling threatened to disadvantage them.

"...A huge problem on campus is that offices don't communicate, like Title IX does not collaborate with housing or the registrar and it causes big issues," Me Too Marist said.

The anonymous Me Too Marist account explained in a direct message how a former roommate got into a physical altercation with their significant other - the girlfriend suffered a sprained wrist and fractured ribs. The abuser was not suspended despite Me Too Marist's first-hand account of the incident to Title IX.

"Virtually no consequences - she had to take a dating violence course. Well when housing time rolled around, the two of them wind up in the same house, then the next semester somehow wind up in a few of the same classes," Me Too Marist wrote. "The registrar and housing basically said to the survivor in the situation their hands are tied and the situation was dealt with and she received her consequences - basically telling her to get over it or drop out of housing and those classes."

Eight anonymous students were interviewed on their sexual assaults in 2018 by the Circle

And everyone seems to know a version of this type of story.

"Based on what I’ve heard, no, [Title IX doesn't] take the proper care," said Marist Democrats president Rosemary DaCruz. "They don’t enforce no contact orders, they don’t ensure that students aren’t in class with their abusers. I know of several circumstances where survivors were actually placed on the same floor or dorm building as their rapists."

The general consensus increasing becomes more and more difficult to ignore, as DaCruz distinguishes "Marist will not act unless pushed very far", habitually practicing a "reactive, not proactive" pattern.

"I have yet to hear of anyone who was satisfied by the Title IX process in regards to their situations here," Leavitt said.

The It's On Us chapter president disclosed her own traversal of Title IX, where the logic of the reporting system is used against the very same protect groups it was designed for and conditions rendering them vulnerable do not make them "credible".

"When I was a freshman I was sexually assaulted here. I thought that the Title IX process was lengthy however, that happens when there is a legal process," Leavitt said. "The perpetrator was found not guilty because they said I wasn’t a credible source because I was too drunk. But, I feel as though that right there is the problem: If I was too drunk to be a 'credible source' someone should not have been having sex with me.

"As an incoming freshman I was SO excited to become a member of the Marist community and now I am honestly ashamed of the way the school handles very serious situations...I have not seen the perpetrator since then and I have made inkling he doesn’t go here anymore but I know he definitely did not face any consequences for his actions as he was found not guilty."

Gina, a pseudonym of an anonymous victim featured in the the 2018 Circle article, wished she could go back and initially report to the police instead, even when her attacker was found guilty by Title IX.

"I felt like he got away with it. It was wrong. I get that it was a mistake, but you face the consequences for mistakes,” she said, believing the disciplinary consequences he faced to not be severe enough as he continued enrollment at Marist.

After having a rape kit performed at a local hospital the morning following a rape, Gina reported the attack to Marist Title IX with the investigation lasting a total of seven months:

“The process was long, and really draining. It’s just a constant reminder of the trauma you’ve already been through."

Hindsight proves to be a bittersweet indicator of truth behind many assault cases, after the event itself or when actions further escalate. Warning signs of abuse are too obvious after the fact, to which students trapped in prolonged toxic relationships are critical of ignorance to these symptoms.

"And to say the least, as professionals who should be aware of what dating violence looks like and what physical abuse can look like, what mental and emotional abuse can look like, and knowing that these abusers are capable of…they failed me," Magnus said.

In 2018, Freer outlined Marist's plans to devote more resources to fighting sexual assault, among them including hiring a new full-time staff member for the Title IX office. Three years later, there is still none except Daniele, exhibiting a low retention rate.

Excerpts of the 2017-2019 Marist Safety & Security Report, published in December 2020

The Campus Climate

Marist's self-published Safety & Security report from December 2020 shows sexual assault numbers at Marist have doubled since the previous report, according to the statistics of just the cases reported between 2017 and 2019.

The 2014 - 2016 report that was released in Fall 2017 disclosed the campus crime statistics of that three year period, totaling: 12 rapes, 1 fondling, 3 aggravated assaults, 22 burglaries, 1 case of domestic violence, 7 dating violence cases, and 1 instance of stalking.

Over the three years, the 2020 report has total counts of: 25 rapes, 14 fondlings, 23 burglaries, 1 case of domestic violence, 8 cases of dating violence, and 2 instances of stalking.

And these are just what is reported, as many assaults can fall by the wayside and never come into fruition as a report.

The Marist Circle predicted an up-tick like this in October 2018 when surmising the 2017 report's information pointed to a more common, growing trend. Director of Safety & Security Blaisdell stated, "I believe sexual misconduct is underreported and we would like to have it reported."

A large portion of the anonymous students from the 2018 Circle feature were generally unsure of how to file a report.

The 2014 - 2016 Safety & Security Report's statistics, published in December 2017

"The bigger issue is...so many students don’t even know about Title IX or who to turn to when they have a Title IX issue," wrote Marist FEMME. "It’s stigmatized in the sense that it’s just doesn’t feel like public information for students and we wouldn’t know how to go about filing a Title IX report, what it entails, or who to talk to, and I think that turns a lot of students off because they don’t know how to handle this discreetly. "

Marist claims it does its best to advertise its resources and Title IX services, but social media posts and emails that go unread are minimal. The likelihood of students internalizing information from physical media such as flyers or signs decreases during periods of stressed remote learning even during in-person semesters.

“The bottom line as I see it, from both my time there and reviewing current comments from students, is that Marist loves to offer all their resources to any student who needs help,” said Hull, a class of 2011 alumni. “The truth is though that the resources that are needed...fall tragically short because the college cares more for athletic budgets and constant campus expansions more than they care about the basic needs of the students.”

Online commenters admitted the Title IX promotional posters in campus bathrooms are normally torn down, sometimes even in the women's room

"I asked [Marist executives] about having a social media presence to make students more aware and they did not want to work with me on that idea," said Grace Leavitt.

While rape and domestic assaults consistently increased over the past six years, on-campus alcohol and drug violations remained stay over those years. On average, 67.5 drug abuse and 483.6 liquor law violations occurred each year from 2014 to 2019.

"I know a lot of people don't even realize that they were sexually assaulted or harassed," Marist FEMME said about students discounting intoxicated behavior when participating in rowdy party culture. "Especially since Marist is a bar school and that's the party attraction, it's extremely common."

The culture of the campus is typically as obvious as people make it, with students passing down observations to younger classes.

"Honestly in the broad sense, students are very much aware of the climate," sophomore Karina Brea said. "I was told by multiple people my freshman year which houses to go to and not to go to if I didn’t want to get drugged."

Marist Me Too, It's On Us, and Marist FEMME put on an exhibition titled "What Were You Wearing" in the Student Center in October 2020, where the outfits matching anonymous respondents' descriptions of what they wore during an attack were hung on a clothing rack. From going out attire to sweats or gym wear, the interactive installation exemplified the randomness of sexual violence and diffused biased rationales that women can be blamed for their own victimhood.

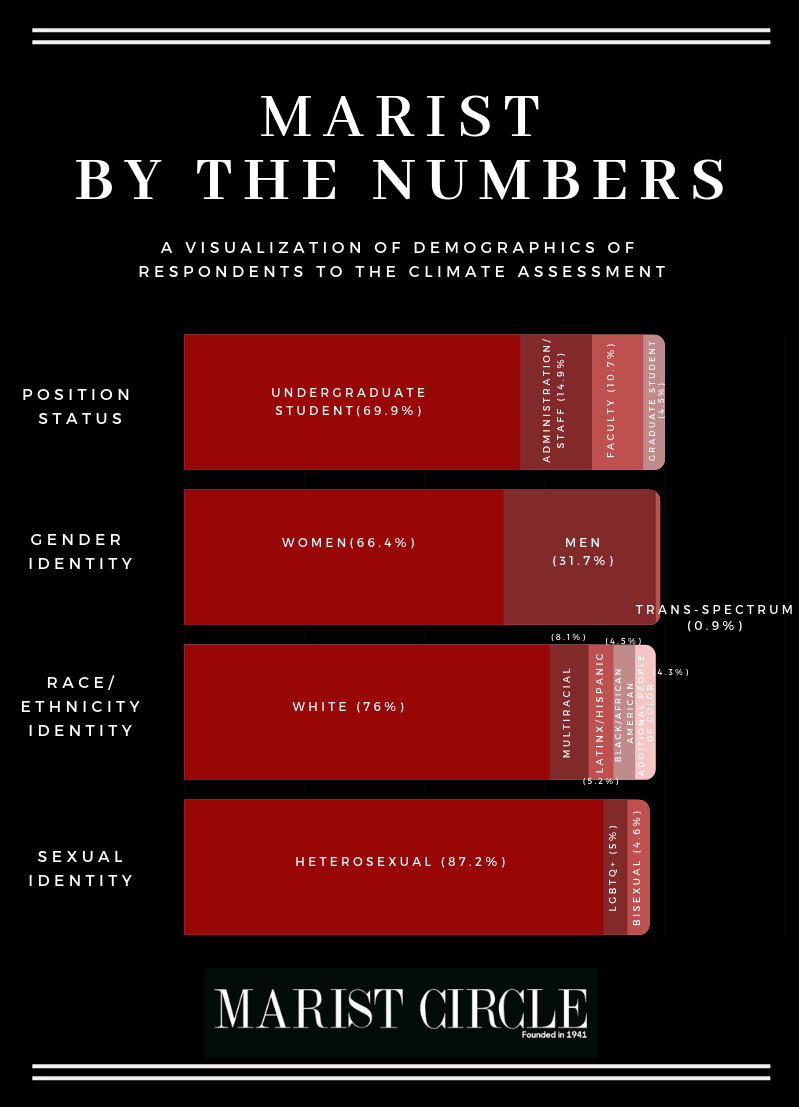

While the Title IX office never published findings from its "Marist College 2018 Sexual Assault Climate" survey, the college did publish its annual Assessment of Climate for Learning, Living, and Working Survey in 2019.

Student critics read that while the survey indicated "80 percent of students were 'comfortable' or 'very comfortable' on campus", the attitudes of campus demographics varied.

Among the 2,249 respondents, 48 percent of trans-spectrum and 27 percent of multiracial respondents cited experiencing "exclusionary, intimidating, offensive, and/or hostile conduct within the past year."

"I personally am a queer student, and I have been contacted to participate in a round table discussion about the LGBTQ+ community on campus, in which we were able to give some feedback about the campus culture and climate," said Rosemary DaCruz. "In my circumstance, I left my meeting feeling happy they wanted to hear me, and then spent the rest of my time being just as mistreated as I had before."

DaCruz saw no "tangible steps" being taken for Title IX reform following these meetings. The Marist Democrats president's only experience with Title IX was their reporting of homophobia and transphobia.

An excerpt from the same article highlights the sexual assault climate and student apathy or distrust of the Title IX reporting systems. Ten percent of respondents indicated unwanted sexual conduct/contact in their time at Marist, which included relationship violence, stalking, unwanted sexual contact, and repeated sexual harassments. That is over 220 students.

The assessment stated: "The primary rationale cited for not reporting these incidents was that the incidents were no severe enough to merit reporting. Other rationales included fears associated with the reporting process and a lack of faith in the outcomes of reporting."

For clarity, Marist's demographic numbers they constantly tout measures the female student population to equal 58 percent of the campus, and students of color equating to nearly 25 percent.

"To be candid, it feels as if they throw us 'scraps' so that we have something to feel like progress is being made," DaCruz said. "There are forums about race issues, but still racist professors in classrooms; There is a public 'concern' about sexual assault on campus, but there are so many survivors who feel so ignored."

Akin to the problematic theatre program director Matt Andrews sustaining employment, another petition was launched demanding Judge Edward McLoughlin's termination as an adjunct professor at Marist. In February 2020, McLoughlin sentenced Nicole Addimando to 19 years to life for killing her long-time boyfriend who had subjected her to years of domestic abuse.